|

|---|

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Edward I of England and His Great History-

Early ambitions-

Edward had shown independence in political matters as early as 1255, when he sided with the Soler family in Gascony, in the ongoing conflict between the Soler and Colomb families. This ran contrary to his father's policy of mediation between the local factions. In May 1258, a group of magnates drew up a document for reform of the king’s government — the so-called Provisions of Oxford — largely directed against the Lusignans. Edward stood by his political allies and strongly opposed the Provisions. The reform movement succeeded in limiting the Lusignan influence, however, and gradually Edward’s attitude started to change. In March 1259, he entered into a formal alliance with one of the main reformers, Richard de Clare, Earl of Gloucester. Then, on 15 October 1259, he announced that he supported the barons' goals, and their leader, Simon de Montfort.The motive behind Edward's change of heart could have been purely pragmatic; Montfort was in a good position to support his cause in Gascony. When the king left for France in November, Edward's behaviour turned into pure insubordination. He made several appointments to advance the cause of the reformers, causing his father to believe that his son was considering a coup d'état. When the king returned from France, he initially refused to see his son, but through the mediation of the Earl of Cornwall and the archbishop of Canterbury, the two were eventually reconciled. Edward was sent abroad, and in November 1260 he once more united with the Lusignans, who had been exiled to France.

Back in England, early in 1262, Edward fell out with some of his former Lusignan allies over financial matters. The next year, King Henry sent him on a campaign in Wales against Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, with only limited results. Around the same time, Simon de Montfort, who had been out of the country since 1261, returned to England and reignited the baronial reform movement. It was at this pivotal moment, as the king seemed ready to resign to the barons' demands, that Edward began to take control of the situation. Whereas he had so far been unpredictable and equivocating, from this point on he remained firmly devoted to protecting his father's royal rights. He reunited with some of the men he had alienated the year before — among them his childhood friend, Henry of Almain, and John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey — and retook Windsor Castle from the rebels. Through the arbitration of King Louis IX of France, an agreement was made between the two parties. This so-called Mise of Amiens was largely favourable to the royalist side, and laid the seeds for further conflict.

"Edward I" redirects here. For other kings who might be known by this name, see King Edward.

| Edward I Longshanks | |

|---|---|

| |

| Portrait in Westminster Abbey, thought to be of Edward I | |

| Reign | 16 November 1272 – 7 July 1307 (34 years, 233 days)&0000000000000034000000&0000000000000233000000 |

| Coronation | 19 August 1274 |

| Predecessor | Henry III |

| Successor | Edward II |

| Consort | Eleanor of Castile m. 1254; dec. 1290 Margaret of France m. 1299; wid. 1307 |

| Eleanor, Countess of Bar Joan, Countess of Hertford Alphonso, Earl of Chester Margaret, Duchess of Brabant Mary of Woodstock Elizabeth, Countess of Hereford Edward II of England Thomas, Earl of Norfolk Edmund, Earl of Kent | |

House | House of Plantagenet |

| Father | Henry III of England |

| Mother | Eleanor of Provence |

| Born | 17/18 June 1239 Palace of Westminster, London, England |

| Died | 7 July 1307 (aged 68) Burgh by Sands, Cumberland, England |

| Burial | Westminster Abbey, London, England |

Edward I (17 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons. In 1259, he briefly sided with a baronial reform movement, supporting the Provisions of Oxford. After reconciliation with his father, however, he remained loyal throughout the subsequent armed conflict, known as the Second Barons' War.

After the Battle of Lewes, Edward was hostage to the rebellious barons, but escaped after a few months and joined the fight against Simon de Montfort. Montfort was defeated at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, and within two years the rebellion was extinguished. With England pacified, Edward left on a crusade to the Holy Land. The crusade accomplished little, and Edward was on his way home in 1272 when he was informed that his father had died. Making a slow return, he reached England in 1274 and he was crowned king at Westminster on 19 August.

Edward's reign had two main phases. He spent the first years reforming royal administration. Through an extensive legal inquiry, Edward investigated the tenure of various feudal liberties, while the law was reformed through a series of statutes regulating criminal and property law. Increasingly, however, Edward's attention was drawn towards military affairs. After suppressing a minor rebellion in Wales in 1276–77, Edward responded to a second rebellion in 1282–83 with a full-scale war of conquest. After a successful campaign, Edward subjected Wales to English rule, built a series of castles and towns in the countryside and settled them with Englishmen. Next, his efforts were directed towards Scotland. Initially invited to arbitrate a succession dispute, Edward claimed feudal suzerainty over the kingdom.

In the war that followed, the Scots persevered, even though the English seemed victorious at several points. At the same time there were problems at home. In the mid-1290s, extensive military campaigns required high levels of taxation, and Edward met with both lay and ecclesiastical opposition. These crises were initially averted, but issues remained unsettled. When the king died in 1307, he left behind a number of financial and political problems to his son Edward II, as well as an ongoing war with Scotland.

Edward I was a tall man for his era, hence the nickname "Longshanks". He was also temperamental, and this, along with his height, made him an intimidating man, and he often instilled fear in his contemporaries. Nevertheless, he held the respect of his subjects for the way in which he embodied the medieval ideal of kingship, as a soldier, an administrator and a man of faith. Modern historians have been more divided on their assessment of the king; while some have praised him for his contribution to the law and administration, others have criticised him for his uncompromising attitude to his nobility.

Currently, Edward I is credited with many accomplishments during his reign, including restoring royal authority after the reign of Henry III, establishing parliament as a permanent institution and thereby also a functional system for raising taxes, and reforming the law through statutes. At the same time, he is also often criticised for other actions, such as his brutal conduct towards the Scots, and issuing the Edict of Expulsion in 1290, by which the Jews were expelled from England. The Edict remained in effect for the rest of the Middle Ages, and it would be over 350 years until it was formally overturned in 1656.

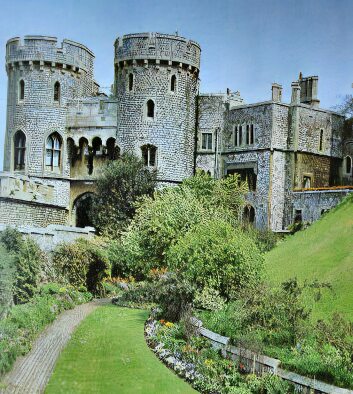

Magnificent Windsor Castle in Berkshire is the oldest and largest occupied castle in the world. Steeped in nine hundred years of history it dominates the surrounding landscape and emanates an impression of power. The castle is one of the Queen's three official residences, the other two being Buckingham Palace and Holyrood House.

The castle was founded by the Norman king, William the Conqueror in 1075. Erected as a wooden mottte and bailey castle on the site occupied by the present Round Tower. The Conqueror's Castle was situated in a strategic defensible position, standing on a hill above a bend in the River Thames at the village of Windlesora, which once formed part of a Saxon royal hunting ground.

The castle was extended by his successors throughout the centuries that followed. William the Conqueror's fourth son, king Henry I replaced his father's original wooden structure with a stone keep. The Round Tower was added by the Conqueror's great grandson, King Henry II, the founder of the Plantagenet dynasty, who replaced the wooden palisade surrounding the old fortress with a stone wall interspersed with square towers. Henry II also built the first stone keep on the irregular mound at the centre of the castle and the first of the castle's medieval state apartments.

Windsor Castle was to experience two sieges in the medieval era. The first occured when the scheming Prince John attempted to take the throne from his absentee brother, Richard the Lionheart whilst the latter was taking part in the Third Crusade to the Holy Land. Windsor was again besieged by the nobles as part of the insurrection which culminated in King John being forced to sign the historic Magna Carta at nearby Runnymede meadow, which is located three miles along the River Thames from Windsor towards London.

Edward III lavished £30,000 on Windsor Castle, the largest crown building project of the Medieval period. He created St. George's Hall, for the use of the knights of the Order of the Garter which he founded on St. George's Day, 1348. Every June, an official gathering of the knights of the Garter takes place at the castle. Following a meal in the Waterloo Chamber, the knights walk in procession headed by the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh, to a service in the chapel.

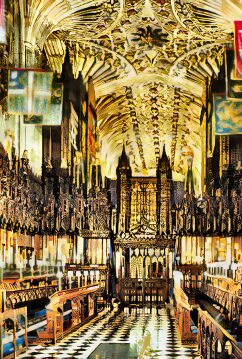

The massive and magnificent perpendicular gothic St. George's Chapel was begun by Edward IV in 1477and completed fifty years later in the reign of his formidable grandson, Henry VIII. It is the burial place of ten British monarchs. Henry VIII and his third wife, Jane Seymour, lie there together with Charles I, beheaded on the orders of Oliver Cromwell in 1649 during the Civil War. Charles was brought captive to the castle by Parliamentary forces prior to his execution in 1649. His body, along with its severed head was later placed in his bedroom, before being buried in the chapel.

The chapel also contains the final resting place of the the martyred Lancastrian king, Henry VI, who lies close to the tomb of his Yorkist supplanter, Edward IV. The last reigning monarch to be buried there was George VI, the father of the present Queen. It is also the final resting place of the Queen Mother.

The chapel also contains the final resting place of the the martyred Lancastrian king, Henry VI, who lies close to the tomb of his Yorkist supplanter, Edward IV. The last reigning monarch to be buried there was George VI, the father of the present Queen. It is also the final resting place of the Queen Mother. The chapel remains one of the finest examples of late medieval architecture and has been the scene of many royal marriages, the latest of these being the wedding of the Earl and Countess of Wessex in 1999.

Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, a new set of State Apartments were built by the Stuart king Charles II, who loved the castle. Charles transformed the medieval castle into a Baroque palace. He rebuilt much of the upper bailey. His apartments were embellished by the work of the famous wood carver, Grinling Gibbons and include ceilings by Antonio Verrio. Charles also added the 5 km Long Walk, leading south from the castle to Windsor Great Park.

That most avid of royal builder's, George IV, had extensive alterations made to the castle in the 1820's. He chose the architect Jeffry Wyatville to built the famous Waterloo Chamber, commemorating the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, which is lined with Sir Thomas Lawrence's famous state portraits of the potentates of the time.

When her beloved Albert, the Prince Consort died at Windsor Castle of typhoid in 1861, rumoured to be caused by the state of its drains, Queen Victoria erected the ornate mausoleum at Frogmore, which stands in the grounds of Windsor Great Park, to his memory. She and a number of their descendants, including Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, older brother of George V, now lie at Frogmore with him.

A disastrous fire broke out at the castle on 20 November, 1992, ironically the 45th wedding anniversary of the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh. It started in the Private Chapel when a spotlight placed there by workmen ignited a curtain and spread rapidly to engulf many of the State Rooms. The fire lasted for fifteen hours destroying nine of the principal State Apartments.

An extensive restoration programme was embarked upon, using authentic materials and craftsmanship. Restoration works were completed five years later, on 20th November, 1997 at a cost of 37 million pounds. A large percentage of the money (70%) was raised by opening Buckingham Palace to the public.

The State Apartments are open to visitors. Windsor houses the major artworks in the royal collection which includes works by Holbein, da Vinci, Rubens, Rembrandt and van Dyck.

The royal family visit Windsor frequently, the Queen regularly spends weekends there and it is used for ceremonial visits from Heads of State.

Admission Information-

Open:- daily, Mar-Oct, 9.45 - 17.15 (last admission 16.00) Nov - Feb, 09.45 - 16.15, (last admission 16.00)

Closed:- 14 & 19 June, 25 & 26 Dec.

Price:-

Adult £13.50

Child £7.50

Concession (Senior/Student) £12,

Family tickets (two adults and up to three children) £34.50 Contact :- Telephone 020 7766 7304

Reign:

Administration and the law-

Upon returning home, Edward immediately embarked on the administrative business of the nation, and his major concern was restoring order and re-establishing royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father. In order to accomplish this, he immediately ordered an extensive change of administrative personnel. The most important of these was the appointment of Robert Burnell as chancellor, a man who would remain in the post until 1292 as one of the king's closest associates. Edward then proceeded to replace most local officials, such as the escheators and sheriffs. This last measure was done in preparation for an extensive inquest covering all of England, that would hear complaints about abuse of power by royal officers. The inquest produced the set of so-called Hundred Rolls, from the administrative subdivision of the hundred.

:Groat of Edward I (4 pence)

The second purpose of the inquest was to establish what land and rights the crown had lost during the reign of Henry III.

The Hundred Rolls formed the basis for the later legal inquiries called the Quo warranto proceedings. The purpose of these inquiries was to establish by what warrant (Latin: Quo warranto) various liberties were held. If the defendant could not produce a royal licence to prove the grant of the liberty, then it was the crown's opinion – based on the writings of the influential thirteenth-century legal scholar Bracton – that the liberty should revert to the king.

By enacting Statute of Gloucester in 1278 the king challenged baronial rights through a revival of the system of general eyres (royal justices to go on tour throughout the land) and through a significant increase in the number of pleas of quo warranto to be heard by such eyres.

This caused great consternation among the aristocracy, who insisted that long use in itself constituted license.Richard I, in 1189. Royal gains from the A compromise was eventually reached in 1290, whereby a liberty was considered legitimate as long as it could be shown to have been exercised since the coronation of King Quo warranto proceedings were insignificant; few liberties were returned to the king. Edward had nevertheless won a significant victory, in clearly establishing the principle that all liberties essentially emanated from the crown.

The 1290 statute of Quo warranto was only one part of a wider legislative effort, which was one of the most important contributions of Edward I's reign. This era of legislative action had started already at the time of the baronial reform movement; the Statute of Marlborough (1267) contained elements both of the Provisions of Oxford and the Dictum of Kenilworth. The compilation of the Hundred Rolls was followed shortly after by the issue of Westminster I (1275), which asserted the royal prerogative and outlined restrictions on liberties. In the Mortmain (1279), the issue was grants of land to the church. The first clause of Westminster II (1285), known as De donis conditionalibus, dealt with family settlement of land, and entails. Merchants (1285) established firm rules for the recovery of debts, while Winchester (1285) dealt with peacekeeping on a local level. Quia emptores (1290) – issued along with Quo warranto – set out to remedy land ownership disputes resulting from alienation of land by subinfeudation. The age of the great statutes largely ended with the death of Robert Burnell in 1292.

From Wikipedia-

0 Comments:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)